Back to Seattle's

Most Interesting Bars

The Black & Tan Club, 1922-1966

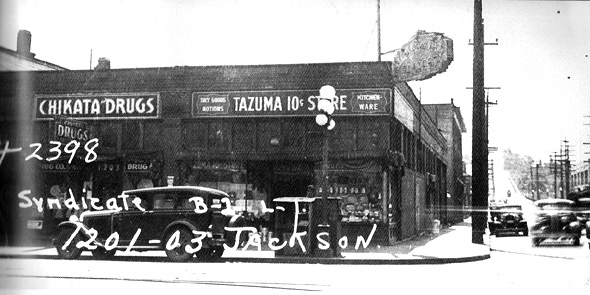

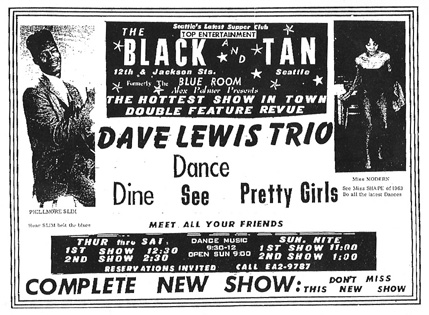

The Black and Tan Club, in the basement of the Entertainers Club at 12th and Jackson, was Seattle's premier nightclub of the 40s and most legendary jazz club. As remarkable as the club itself was, a review of its history also provides a chance to revisit the astonishingly vibrant -- and virtually forgotten -- swing and jazz scenes up and down Seattle's Jackson Street in the 20s through 40s.

The Black and Tan was first opened as the Alhambra club in 1922, by Blackie Williams and Seattle's king of the jazz scene, Noodles Smith (a "black and tan" was a generic name for a nightclub that admitted both blacks and whites). By 1932 it was "known as Seattle's most esteemed and longest-lived nightclub." (de Barros)

"Every kid who grew up in Seattle in the 50s and 60s knew the Black and Tan as the hub of Seattle soul music." But few of them knew that before then, the B&T had hosted the likes of Eubie Blake, Duke Ellington, Charlier Parker, Count Basie, and Ray Charles. Indeed few current Seattleites are aware of the rollicking late night swing and jazz scenes (and later bebop, southern blues and R&B) that once populated Jackson and Madison streets. At one point in the 40s there were 34 nightclubs on Jackson between 1st and 14th Avenues, with musicians who knew their chops walking from club to club and playing in.

An agreement forged at the Black and Tan brought the unknown teenager R.C. Robinson to town. R.C. would later cut his first record in Seattle, and change his name to Ray Charles. The scene produced local luminaries like Quincy Jones, Patti Bown, and Bumps Blackwell, while visiting performers would stay at the Golden West Hotel and hang out in the wee hours at their favorite joints, e.g. Nat King Cole at the 908 Club.

All this was largely allowed to flourish by various versions of a Seattle "tolerance policy," which allowed certain illegal activities to carry-on without interruption from authorities except occasional license fees and secret payoffs to local police. Some of the clubs were equipped with alarm bells, pulleys, bars, and escape slides for the few times the political climate got hot and there was a raid (usually those arrested would be back at work the next day).

Of course another reason Jackson was such a focus and jazz and swing was the de facto color line at Yesler Way. Until the 50s and 60s, black musicians were rarely allowed to play in the downtown clubs, and indeed rarely allowed to attend except on special "spook nights." For most of this time, the white musicians union, American Federation of Musicians Local 76, blocked the lucrative downtown clubs north of Yesler from booking any black musicians. This obstacle was finally resolved in 1958 when the black and white musicians unions merged.

There are few vestiges of this world on Jackson Street today. The jazz scene was done in by a combination of factors from post-WWII tastes running to crooners and piano trios, to the rising primacy of rock and roll, to Washington state's Initiative 171, given hotels and restaurants the legal right to sell liquor by the glass. From De Barros:

"The attack on the Jackson Street 'joints' was motivated by greed as much as it was by a desire to uphold the law. Liquor was an extremely lucrative business. Once it was made legitimate (March 1948), the bottle clubs were not only illegal, they were competition to legitimate operators. The state had no intention of sharing the spoils with the old speaks. The city fathers were enthusiastically supported by the Teamsters union in the effort to stamp out competition, as the union recruited bartenders into the hotel-and-restaurant-workers local. Since the new law allowed only restaurants and hotels to sell hard liquor, it was in the owners' and unions' best interests to make sure they maintained a monopoly on liquor sales. On the street, this meant a shift in action from black-owned Central District joints to Italian-owned -- and union-controlled -- cocktail lounges. In the 1950s, jazz fans began to find themselves in downtown clubs with names like the Italian Village and Rosellini's Four-10."

I strongly recommend De Barros's book to anyone who would like to know more about this scene and Seattle's musical history. It has been by far the most informative source I have found, and most online sources rely heavily upon it.

Further References:

Jackson Street After Hours: The Roots of Jazz in Seattle, Paul de Barros

blackpast.org

The Forging of a Black Community: Seattle's Central District, from 1870

Through the Civil Rights Era

PNWBands.com